Dr Broderick Chow on Central's Support for the Rising Waves British East and South East Asian Mentorship Scheme

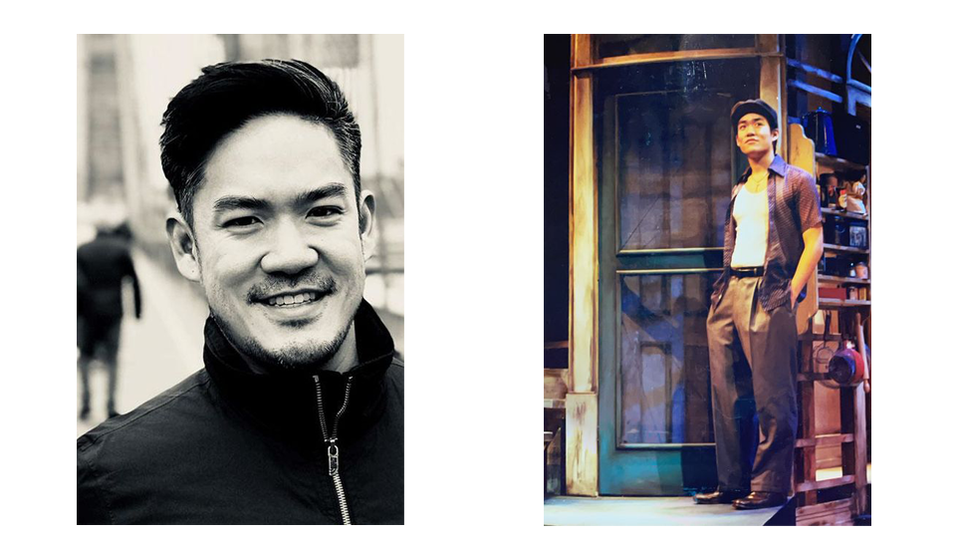

Dr Broderick Chow, Central’s Interim Vice Dean/ Deputy Director of Teaching and Learning; In performance in the University of British Columbia’s production of Tennessee Williams’s ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’

When I was studying at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, my hometown, I took part in some casting that (hopefully) wouldn’t happen today. I played Pablo, a Mexican character, in Tennessee Williams’s A Streetcar Named Desire. I am – in case you were wondering – not Mexican. I knew something was wrong with this, but I was young, and being on the huge stage of the Frederic Wood Theatre was something I’d dreamed about for years. One day, we were rehearsing the famous poker scene and I pointed out to the director that Pablo was required to say a racist slur against Chinese people. “Why don’t you go to the C**** and get us some chop suey?”

I am – if you were wondering again – Chinese. More accurately, Chinese-Filipino.

I told the director I couldn’t say the line.

He nodded and acknowledged that it would probably be a problem. “Just change it to something else, like Greek.”

That was what it was like being an Asian acting student in Vancouver in the early 2000s. During my four years at UBC, I never saw a single Asian actor play a part written for an Asian person in dozens of productions across three stages, even though there were a handful of us in the department.

The industry wasn’t much better. I got an agent in my third year and started auditioning. I got to know a group of about ten to twelve other Asian Canadian guys pretty well. I’d see them nearly every week while we sat on the synthetic chairs outside casting director offices and joke about the parts we were reading for: “Computer Technician”, “Vietnamese Gangster 2” (I actually booked that one).

In 2005, I played the role of Thuy in the Arts Club Theatre Company’s Miss Saigon in Vancouver, Canada, my hometown. It was my first professional production at Vancouver’s largest Equity theatre, and I was delighted to be appearing with a cast of Asian Canadian actors from across the country. Miss Saigon was also the show that eventually made me decide to move to the UK. When it was over, I thought to myself, what else is there? I’d played one of the biggest musical roles specifically written for an actor like me in what is, let’s face it, a pretty dodgy show. Outside of my castmates in Saigon I rarely saw any Asian actors on the Vancouver stage, so it was hard to see a future there.

Coming to the UK and studying on the MA Advanced Theatre Practice at Central was a way of reclaiming my voice, of telling my own stories. I went on to perform for many years as a stand-up comic, I made dance theatre, and I eventually started the academic career that has brought me back to Central in my current role as Interim Deputy Dean.

In 2012, along with a huge number of East and Southeast Asian actors and industry professionals, I was horrified to see the casting announced for the Royal Shakespeare Company’s The Orphan of Zhao. This 13th century Chinese drama, adapted by James Fenton and directed by Gregory Doran, was intended to be the RSC’s first “Chinese” story. However, only three British East and Southeast Asian (BESEA) actors were cast in the show, playing a maid, guards, a puppet dog, and a ghost. The leading roles were played by white actors. We weren’t even allowed to tell our own stories. I was part of an ad-hoc group, British East Asian Artists, which also included Moongate Productions co-founders Daniel York Loh and Jennifer Lim, poet Anna Chen, and actress and writer Lucy Sheen, to name a few, which put pressure on the RSC. We wrote letters, articles, and generally stirred up… stuff. But it wasn’t just us. A community came together in response to this act of erasure. We continued to protest yellow face and other racist representations on stage, but nine years on from that event, the future feels hopeful. The past few years have seen huge successes for BESEA artists, with ESEA centred stories such as the RSC’s Snow in Midsummer, Forgotten at the Arcola,or the Royal Court’s Pah-La (starring Central alumna Millicent Wong), the success on screen of actors like Gemma Chan and Andrew Koji, and the formation of new companies like Papergang Theatre, founded by my ATP classmate Clarissa Widya.

It feels like we’re finally beginning to “see ourselves” after decades of erasure in British theatre and media, which is why Rising Waves, a new free mentorship scheme for BESEA graduates and new entrants into the performing arts industry is so important. I’m proud that Central is a sponsor and supporter of the scheme, which gives BESEA artists, performers, and other creatives the opportunity to be mentored by people from our community.

We know that BESEA people face specific barriers to representation. Despite the success we’ve had as a community since The Orphan of Zhao, BESEAs still remain severely underrepresented in the arts. Moreover, when we are “included”, we are often unheard (literally playing silent parts), secondary (playing roles in service of the protagonist), or stereotyped (as the “model minority” or “perpetual foreigner”). It’s hard to even prove our under representation is a problem, since we don’t really show up in government statistics, certainly not as BESEA. We’ve never officially been able to claim that identity, since government equalities monitoring only recognises “Chinese” or “Other.” In public, acts of racism and hate crimes against BESEA people have risen three-fold since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, while Filipino/a health workers have died from COVID-19 at a staggering and disproportionate rate. Erasure continues — just last month the BBC1 drama The Serpent premiered. Despite being filmed across Southeast Asia, the based on true events show erases the fact that its principal lead, Charles Sobhraj, was half-Vietnamese.

I’d encourage every BESEA artist, creative, and technical practitioner making steps into the industry, whether recently graduated from Central or elsewhere, to apply to Rising Waves. While I can mainly speak from my experience as an actor, the scheme is suitable for artists working across a number of disciplines. This form of targeted mentorship is crucial for us to continue to tell our stories. It’s the kind of scheme I wish I’d had in Vancouver but which I’m delighted to support today.