Race, Motion Data, and Artificial Intelligence Gathering #2

Central staff Kate Elswit and Tia-Monique Uzor talk about their recent international gatherings, leading conversations about motion data.

Performance Lab and the gatherings

At the end of September, Central’s Performance Lab sponsored the second in a series of international gatherings that aim to center dance-led knowledge in conversations surrounding the politics and practices of motion data, amidst a rapidly changing technological landscape. These gatherings are focused on facilitating discussion around motion data in dance, the potential impacts of machine learning and generative AI on our field, and how considerations of race, privilege, and power are–or should be–influencing approaches to investigations in this area.

The first gathering was held in August at The Ohio State University’s Advanced Center for Computing in Arts and Design, convened by Crystal Michele Perkins on behalf of Archiving Black Performance: Memory, Embodiment, and Stages of Being and Harmony Bench for Visceral Histories, Visual Arguments: Dance-Based Approaches to Data, and sponsored by OSU’s funding for Artificial Intelligence in the Arts, Humanities, and Engineering: Interdisciplinary Collaborations.

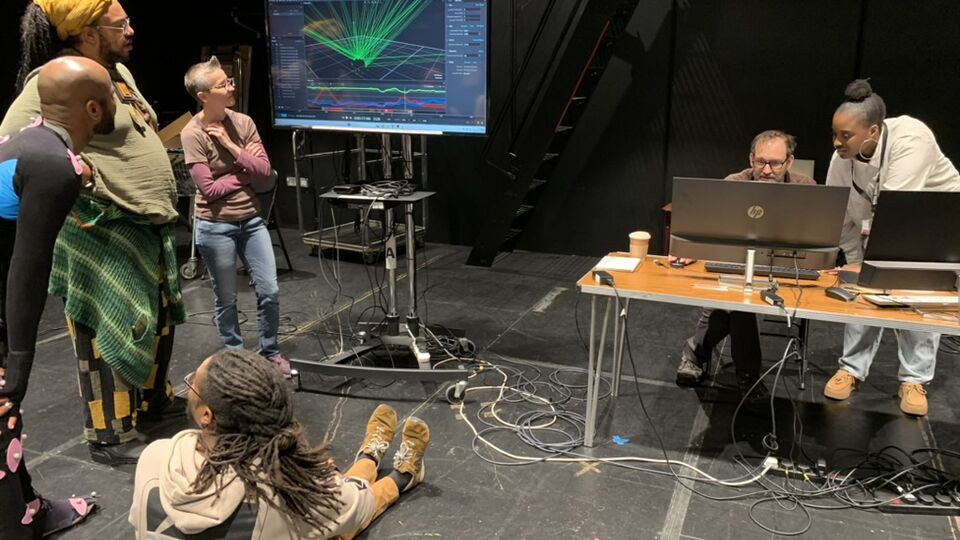

This second gathering was convened by Tia-Monique Uzor, PI on Digital Black Dance Ecologies, which was recently funded through the AHRC’s Dance Research Matters Network call, together with Kate Elswit for Visceral Histories, Visual Arguments: Dance-Based Approaches to Data, and took place across Central’s studios and new Motion Lab. Invited participants brought their expertise from professional practice, teaching, curation, and academic research to shape the discussion and practical explorations: Harmony Bench, Omari “Motion” Carter, David Gochfeld, Antoine Marc, Joumana Mourad, Teoma Naccarato, Nicola Plant, and Thomas “Talawa” Prestø.

What were the themes you explored?

A key theme of the day was the delicate balance of pace in terms of reflecting on the enduring impacts on culture and society, even as we adopt cutting-edge technologies. There was a strong emphasis on harnessing new technologies to remain competitive in both industry and artistic pursuits, including having to quickly generate new teaching materials. Concurrently, there also was an investment on countering ‘colonial spacetimes’ (Noxolo in 2023), where society advances with detrimental practices in the name of innovation, only to reflect on the consequences decades after the harm has already been inflicted. At the same time as we discussed methods for slowing down to reflect within our practices — including bringing forward a conversation from the first Ohio gathering about “moving at the speed of trust” when working in community — participants in London also explored the tactical uses of fast motion, particularly in the context of working within institutional settings.

Another prominent theme was addressing AI bias in the contexts of our work. This included conversations on both invisibility (for example, how most pose estimation models are not trained to process the data necessary to represent Black dance and dancers), and also hypervisibility (for example, how “African dance” is being used in Midjourney prompts to circumvent content restrictions around nudity). We spoke about how our practices negotiate the tradeoffs of being visible to algorithmic processing versus the harms of surveillance and extraction.

In the motion capture studio, Antoine kindly allowed markers to be placed and re-placed on him, as participants explored the system’s default capture settings and experimented with different approaches to make it more sensitive to an array of dancing bodies. For example, while critiquing the need for a broader diversity of skeletal representations, Thomas shared a calibration hack for the automatically-generated avatar to better represent the pelvic tilt and lumbar spinal motion needed to gather more usable data related to West African dance. We discussed distinctions between the dancer and avatar, and the base thresholds for representation, even given the labor-intensive possibilities of motion re-targeting.

We drew the day to a close by collectively reading the Feminist Data Manifest-No, followed by discussion that explored potential applications and adaptations of the Manifest-No’s principles to our own practices and motion data more broadly. This reflective exercise served as a valuable culmination of the day of thought-provoking dialogue and inquiry.

Thanks to all involved so far

This series of co-hosted gatherings arose because we were encountering challenges in our own research that tied into the critical conversations so many dance folks are grappling with at the intersections of race, motion data, and artificial intelligence today. We are grateful to everyone to date who has taken the time to think with us, to share experiences and expertise, and to pool resources, and we look forward to ongoing discussions.